In 1994 Marie Diongoye Konate bought an old milling machine and set up a small food processing business in a corner of a popular market in Abidjan, capital of Cote d’Ivoire. Born in Mali and educated in Switzerland, she had gone to Cote d’Ivoire to work on a government-financed soya project.

Aside from earning a living and helping to advance the local agro-industry, she wanted to prove a critical point.

“I created a social business to spur development. My goal was also to create a business model for others—for young people, young Africans. I was trying to prove that it was possible to start small, very small, and to win,” she said earlier this month in Washington, D.C.

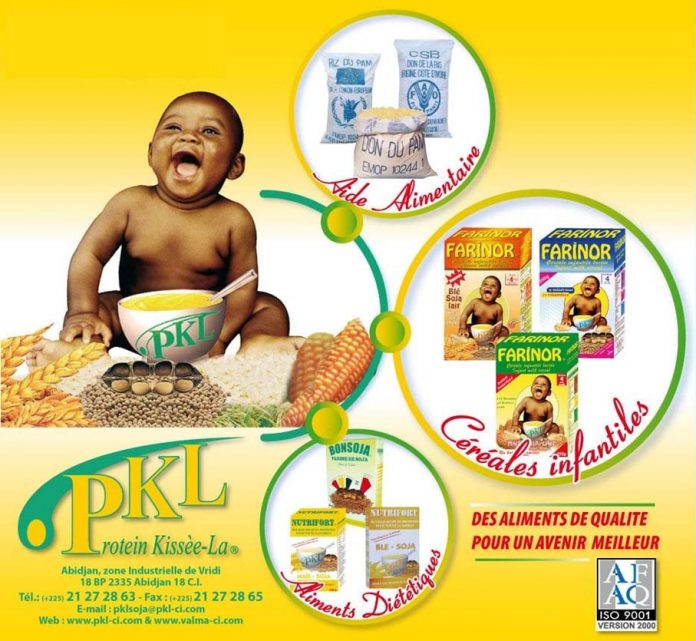

Thirty years after founding Protein Kissee-La (PKL) S.A., now a multi-million-dollar producer of cereals made with local ingredients and supplier of food aid to the African market, Konate traveled to the United States as a CEO delegate to the White House-organized U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

She came with a lot to say.

“I’m an African. Proud to be an African. But I’m sick of hearing that Africans do nothing for themselves. We have the capacity, we have the intelligence, we have the means, but most of the time we don’t have the right government,” she told a rapt audience in the U.S. Capitol Congressional Auditorium on the last day of the three-day, first-of-its-kind summit.

“While I’m here, what is the message that I want to share? It’s that the SME, the small and medium enterprise, is the solution for the development of Africa. I am here to convince the Diaspora—the young students here in America—that they can go back to our countries. We need them. There are lots of opportunities in Africa. But I know also that the continent lost opportunities. We are not getting to transform those opportunities into reality.”

Konate made her heavily French-accented remarks at the “Dialogue with African CEOs” hosted by U.S. Congressman Gregory W. Meeks and the Africa Task Force of the Congressional Black Caucus as a side event to the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

“I started my business with $500. I had much more in my pocket. Five hundred dollars. I never had any business training. I am an engineer-architect from Switzerland, which has nothing to do with nutrition and food. But I didn’t feel like building ministers’ houses. I was looking for a useful business, and of course a profitable business,” she said.

It took time to find the right business.

“I chose agribusiness, thinking that we Africans have many food problems. In Africa we export what we produce and we import what we consume. It’s very stupid,” Konate said.

She had worked in Brazil where, she has observed, Brazilians eat what they produce. Cereals are among the top five U.S. exports to sub-Saharan Africa. In 2013 they were the fifth largest U.S. export to the region—behind machinery, vehicles, mineral fuel and aircraft—at a total value of $1.3 billion. Exports of all U.S. agricultural products to the region totaled $2.6 billion the same year, led by wheat ($1.1 billion), poultry meat ($513 million), rice ($94 million), vegetable oils (excluding soybean oil; $95 million), and coarse grains ($89 million).

When Konate launched her business in Abidjan, there were no African cereals or baby food on the shelves, only imported products, which were made mostly with corn and soy—crops widely grown in Cote d’Ivoire and throughout Africa.

“Between the local market and the giant next door in Ghana, there was a big gap to fill. So I planned to offer highly nutritional food at an affordable price to African poor classes and middle classes,” Konate said.

Health statistics validated her choice of business. In Côte d’Ivoire, more than 30 percent of five-year-old children suffer from moderate to severe malnutrition, she explained. PKL would produce local infant cereal, while benefiting local farmers.

“So now, 30 years later, my company, PKL, produces baby food, food aid, food for people dealing with HIV. The company employs 35 people, with seven experienced engineers. We have international quality certification,” Konate said. “It’s a very small company. The turnover is around $3 million to $5 million, depending on when there is war and when there isn’t war.”

Although her business model clearly works—identify an area of need; start small; grow steadily even if slowly; support local industry—the model has not attracted as many young entrepreneurs as Konate would have liked.

“Our young in Africa, they are in a hurry to earn money. All of them want to be millionaires,” she lamented. “But they just forget one thing: they need to work, and work, and work hard. We want to reach heaven. But to reach heaven you have to die first. Die at least a little bit. This is my message.”

In 2006, PKL died “a little bit” when toxic waste unloaded by a Dutch-chartered ship in the Port of Abidjan was dumped close to PKL’s premises, forcing Konate to briely close the business. Damage to the economy from post-election violence in 2010 through early 2011 further impacted the business, but Konate stayed the course, confident in the future.

In Washington, she had a message, too, for members of the U.S. Congress.

“I want to say to the Congress [to adopt measures that would help] to stimulate the development of the SME in Africa.”